For decades Nigeria has endured a brutal paradox of sitting atop vast crude reserves while its citizens queue for petrol.

The failure of state-owned refineries at Port Harcourt, Warri and Kaduna, mired in mismanagement, theft and chronic underinvestment had allowed foreign refiners, importers and a shadowy middleman economy to prosper at the nation’s expense.

That rot created a political and commercial ecosystem that benefited a few while costing the country billions in foreign exchange and predictable, affordable fuel supply.

It is against this shameful backdrop that the Dangote Refinery ought to be celebrated and protected, not obstructed by those whose interests are best served by the status quo.

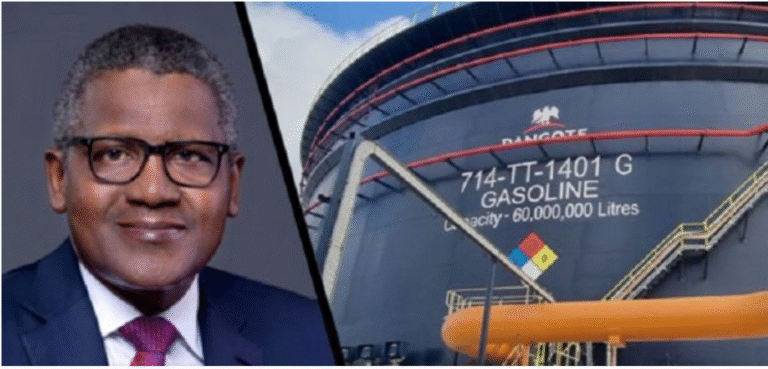

Dangote’s facility is not a mere private refinery; it is a structural corrective. Commissioned in 2023 and designed to process up to 650,000 barrels per day, the plant promises to convert Nigeria from a perennial importer of refined products into a supplier for West Africa and beyond.

Early shipments and commercial deals already show the refinery can meet international specifications and reach global markets, shifting trade flows that once enriched foreign refineries and importers.

This is the concrete leap the country needs to stop bleeding foreign exchange and to stabilise domestic prices.

So why the pushback?

Some of it is predictable — legitimate concerns about market conduct, contract terms, and disruption of established businesses. But much of the resistance flows from entrenched interests who benefited enormously from the old import-dependent model.

For decades, depot owners, importers and the middlemen who controlled distribution networks relied on steady imports funded by subsidy arrangements and opaque government procurement.

The arrival of a reliable, mass-refining domestic supplier threatens those rent streams.

That explains the ferocity of some of the opposition: it is not only economic competition, it is an existential threat to vested players.

It is also why we must scrutinise loudly voiced claims that seek to characterise the refinery’s competitive pricing as predatory rather than as the natural, consumer-friendly effect of domestic capacity.

We must also be realistic about the state’s role. For decades, billions earmarked for rehabilitation of state refineries were squandered or poorly managed; fixes rarely lasted because the underlying incentives, political interference, patronage, and weak accountability were never addressed.

That record is well documented and helps explain why private investment, with a clear balance sheet and accountability to shareholders, was the only credible path to a modern, functioning refinery.

The criticism that Dangote’s arrival will “monopolise” the market ignores the fundamental point- a functioning large refinery is what breaks dependence on imports and gives the policy space to end distortionary subsidies and mend the currency.

Practical politics matters too

The government’s decision to end the state oil firm’s exclusive right to buy Dangote products and to allow private traders to purchase directly was a welcome move toward market efficiency.

It recognises that the refinery should supply markets, not be constrained by legacy procurement arrangements that reproduce inefficiency.

But policy shifts alone are not enough. The state must also defend new capacity from deliberate disruption, whether it be industrial action aimed at paralyzing operations or calculated accusations that serve to delegitimise the refinery’s competitive offers.

Recent public spats between marketers’ associations, unions and Dangote have already risked distracting the nation from the larger prize- a self-sufficient refined-products industry and the macroeconomic gains it brings.

What should be done?

First, the government must build a firewall between legitimate regulatory oversight and vested political interference. Investigations into market conduct must be transparent, independent and speedily concluded, not weaponised to stall operations.

Second, authorities should accelerate policies that integrate domestic refining into national fuel security plans: guaranteed access to crude through transparent, naira-denominated arrangements where necessary; removal of policy distortions that encourage hoarding; and infrastructure investment in evacuation and distribution to unlock the refinery’s full value to the economy.

Third, marketers, depot owners and truckers must be offered a dignified path to participate: logistics, storage, regional distribution and last-mile delivery are critical functions that will remain even as import margins compress.

Those legacy players who choose collaboration over obstruction will survive and likely thrive.

Finally, Nigerians should judge the Dangote Refinery by results. Will it reduce the billions we spend importing finished products? Will it stabilise supply and reduce the urgency of the forex chase that drives petrol panic and price spikes? Early signs are promising: exports, regional interest and the scale of production suggest real change is happening.

To throw up roadblocks now, whether rhetorical, legal, or physical is to gamble away a rare chance to fix a policy failure that has plagued generations.

The past showed that state ownership, without accountability, produced rusting pipelines, idle plants and recurring crises.

The present offers a market-driven remedy. For the sake of millions of Nigerians, for the health of the naira, and for the country’s economic sovereignty, we should stand with the refinery that finally shows the promise of self-reliance. Protect the refining revolution.