In Kano State, 20 year old Kamilu Samaina had just delivered her baby at home. After a grueling 15 hour labor with a traditional birth attendant, she began hemorrhaging. Her relatives rushed her by car to the nearest clinic, but by the time they arrived, Samaina had bled to death in her brother’s arms. In villages like Unguwarbai and Gurduba, such tragedies are routine. Local leaders say at least one pregnant woman dies every month. These deaths often come from preventable causes such as severe bleeding, untreated high blood pressure, or delays in reaching care.

On paper, Nigeria’s Basic Health Care fund should have been a lifeline for mothers in places like this. But corruption and poor management have crippled it. In Gurduba, for example, the local clinic is stocked with equipment and even has a generator. Yet villagers say there is “no staff to take delivery” on hand. With no trained professionals, many women still deliver at home or turn to traditional birth attendants. Meanwhile, wealthier Nigerians go to private hospitals or even fly abroad, showing the gap between rich and poor.

In Lagos, a young pregnant woman known as Kemi collapsed from eclampsia. Her husband rushed her to a private clinic, but staff allegedly refused to admit her without a ₦500,000 ($625) deposit. He did not have the money and Kemi died in February 2025 while being transferred to a public hospital. The incident, caught on video, is now under investigation, but for her family it is already too late.

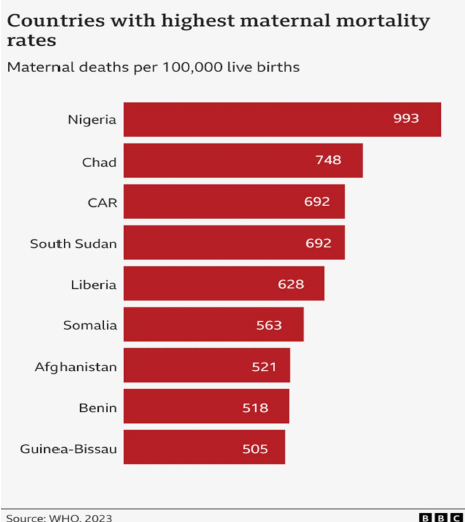

Nigeria has the highest maternal death rate in the world. About one in every 100 women dies during childbirth. In 2023 alone, nearly 75,000 Nigerian mothers died, almost a third of all global maternal deaths. UNICEF reports that Nigeria contributes around 10 percent of the world’s total, with a maternal mortality ratio of 576 per 100,000 live births. Where a woman lives makes a huge difference. A pregnant woman in the northeast is ten times more likely to die than one in the southwest.

Behind these numbers is a broken health system. Nigeria spends only about 5 percent of its national budget on health, far below the 15 percent target set by African leaders in the Abuja Declaration. U.S. aid for Nigeria’s maternal programs has in some years been larger than Nigeria’s entire federal health budget. Many clinics have no doctors, empty operating theaters, and frequent drug shortages. Corruption and mismanagement mean that even newly built clinics often sit unused. At the same time, thousands of doctors and nurses are leaving the country in search of better pay and conditions abroad.

Inequality makes the crisis worse. In Kano, only about 21 percent of births are attended by skilled health workers, compared to nearly 90 percent for wealthier mothers in cities. The World Health Organization has found that births among Nigeria’s richest families are twice as likely to have professional care as those among the poorest. In poor rural communities, women give birth on dirt floors. In wealthy households, mothers are treated in private hospitals or even overseas. Simply put, where a woman is born and how much money her family has often decides whether she survives childbirth.

The silence from those in power is deafening. Mothers are dying from conditions that could be prevented with basic medicines, safe blood transfusions, and trained midwives. Nigeria’s leaders must back up promises with real funding, honest management, and stronger accountability. Ending corruption, training and supporting health workers, and enforcing existing health policies are urgent steps.

The cost of inaction is clear. Every day, more families are left mourning women who should be alive to raise their children. The question now is whether Nigeria will continue to accept this deadly silence or finally decide that no mother should have to die giving life.

In conclusion, the tragic stories of Kamilu Samaina and Kemi highlight the urgent need for comprehensive reforms in Nigeria’s maternal healthcare system. The government must prioritize increasing health expenditure to meet the Abuja Declaration’s target of 15 percent, ensuring that funds directly support clinics and services in underserved areas. Strengthening the oversight and management of health programs is essential to combat corruption and misallocation of resources.

Additionally, investing in training and retaining skilled healthcare professionals will help bridge the significant gap in maternal care access between wealthy and impoverished communities. It is imperative that the government enforces existing health policies and establishes accountability mechanisms to ensure that every woman, regardless of her socioeconomic status or geographic location, receives the care she deserves. Only through decisive action can Nigeria hope to reverse its appalling maternal mortality rates and fulfill the promise of safe motherhood for all.

See also:

Clean Water, Dirty Politics: Why Cholera Still Exists in Nigeria. By Feyi Akinfesoye

The Rising Power of Prompt Engineering